African literature is a country

What if you survey African literature professors to find out which works and writers are most regularly taught? Only a few canonical ones continue to dominate curricula.

Image credit Suad Kamardeen via Unsplash.

African literary studies today is a site of deep paradox. On one hand, the last two decades have seen astonishing growth for African literature in the global North and South, evidenced by lucrative publishing deals; new prizes and grants; literature festivals; the establishment of many new presses and imprints; and an increase in blogs and platforms that disseminate and discuss these developments. On the other hand, African literature continues to exist on the margins of the academic mainstream and is also underrepresented within larger reading publics.

For example, in a recent attempt to “create a fully digitized corpus of 20th-century fiction” Achebe’s Things Fall Apart was the only African novel repeatedly mentioned. African literatures are usually classified and taught within a continental framework—as in the category of “African literature”—a geographical term that implicitly disregards the myriad regional, national, cultural, and economic differences in a continent comprised of fifty-four countries. Indeed the colonial invention of a composite and singular “Africa” remains as entrenched in academic institutions as it is in the global imaginary. That’s how we came to survey instructors of African literature at the university level to find out which works and writers are most regularly taught in their courses.

We sent out emails to over 250 academics, a majority of whom were listed as members of the African Literature Association in addition to several others drawn from our own professional networks. One-hundred and five individuals replied, mainly residents in the US or Europe, and a number of Africa-based professors also contributed to the study. Here’s what we found.

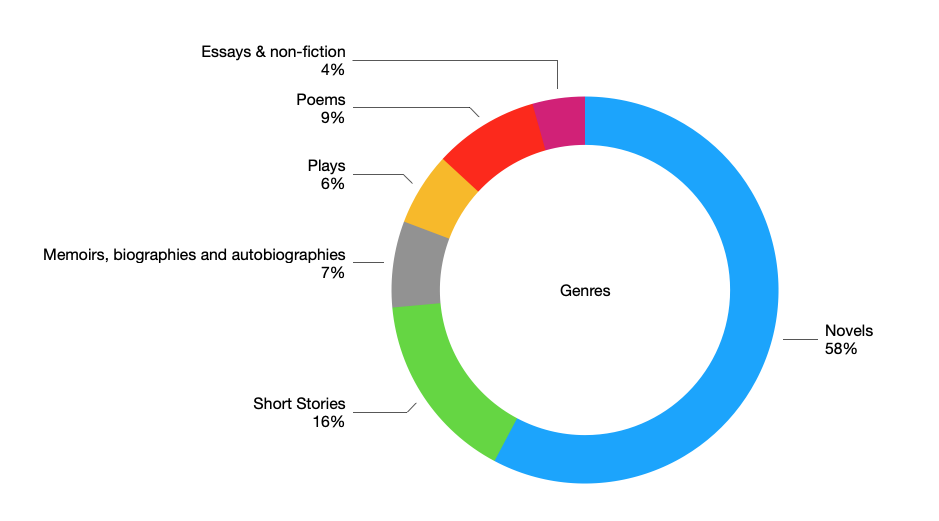

Of the 671 texts that were listed by our respondents, the majority were novels (369) and short stories (101), while memoirs, biographies and autobiographies (46), poems (56), plays (39), essays and non fiction books (28) and anthologies (32) made up the balance.

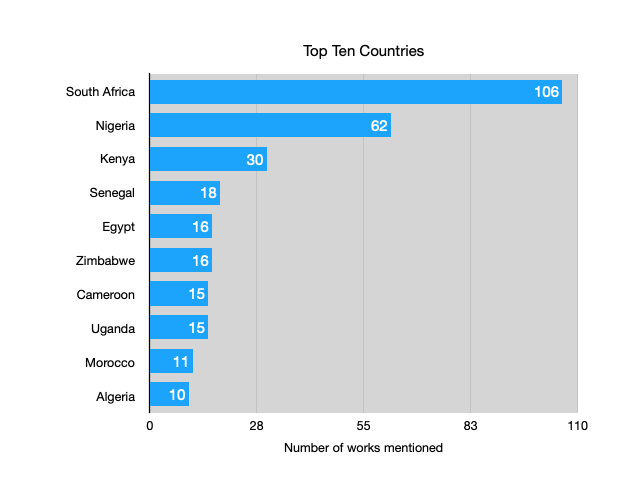

The majority of authors (407) were men (251), followed by women (155). One author identified as non-binary. As for country representation, 45 of the 54 countries that make up the African continent made the cut: South Africa dominated with 106 authors on the list, followed by Nigeria (62) and Kenya (30). Countries with 10 or more books on the list were Senegal (18), Egypt and Zimbabwe (16), Uganda and Cameroon (15), Morocco (11) and Algeria (10). And the total number of languages of assigned texts was 18.

What does all this mean?

Though it was expected that Nigerian and South African texts would dominate the field, we did not anticipate how extreme this would be. Most countries on the continent are represented on curricula by less than five individual texts, whereas 62 Nigerian literary works and a whopping 106 South African are regularly taught.

When it comes to languages, English and French are the source languages of the majority of texts, though a smattering of African languages taught in translation are represented by Acoli, Afrikaans, Arabic, Tigrinya, Xhosa, and Yoruba literary works. A fair number of works written in Spanish and Portuguese are also regularly taught.

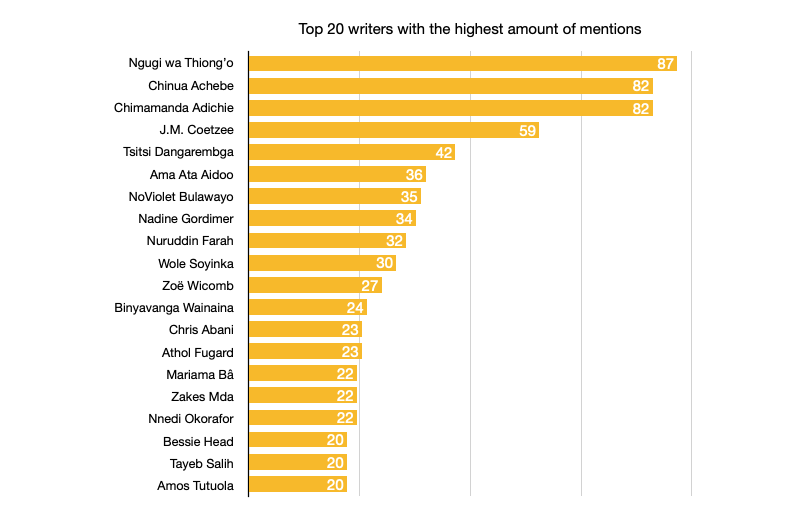

Among authors, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is the most taught writer (87 mentions). Nigerians, Chinua Achebe and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, are similarly popular on syllabi (82 mentions each) while J.M. Coetzee is the next most taught author (59 mentions). Achebe’s novel Things Fall Apart is predictably the most frequently assigned novel, followed by Tsitsi Dangarembga’s Nervous Conditions and NoViolet Bulawayo’s We Need New Names (assigned 42, 40, and 34 times, respectively). That two works by Zimbabwean women rank among the top three most regularly taught novels on college syllabi is an encouraging indication of certain changes afoot. Zimbabwe is thus one of the countries best represented on African literature syllabi. Yet this also reminds us how singular works are often instrumentalized to represent not only an author’s entire body of work, but often her country, and even her continent.

Senegalese writer Boris Boubacar Diop told us that its always the same old texts as well: “African authors are taught in both [Nigeria and Senegal] however they are almost the same ones since the time of independence: Senghor, Beti, Sembene, Kourouma etc. for the ”francophones” et Ngũgĩ, Achebe for the Anglophones. Quite often, one explores the text more often than the novelistic universe; A Grain of Wheat or Things Fall Apart, God’s Bits of Wood, Suns of Independence…Sometimes it feels like students can recite entire passages from these books but also that they only know these.”

Unfortunately, it’s true that only a few canonical works dominate the field, coupled with the near or total non-representation of many important literary traditions including Namibia and Madagascar, to name two countries with rich literary histories that no one mentioned in our survey.

However, this is not a crisis without the potential for transformation. While literary works from South Africa and Nigeria often serve to include African literature in pedagogical efforts to diversify syllabi and include the continent, scholars and teachers of African literature also teach a dizzying number of other works alongside the predictable ones.

Institutional issues

With contemporary debates about decolonizing academic curricula raging in the global North, we wanted to find out where the teaching of African literature is itself positioned within these discussions. The analysis and criticism that follows is therefore primarily directed towards European and North American institutions.

African literary studies often produces institutional quarrels at departmental levels since it is taught within constrained spaces. Most regularly taught in English and Comparative Literature departments, African literature has also historically found a tenuous home in area studies units. Comprising widely diverging percentages of curricula, it is nonetheless fair to say that, in general, African literature constitutes a very small part of what students are offered in most Euro-American literature departments, and is rarely, if ever, required.

In contrast, European and American literature is often sub-specialized into regions, historical periods and single author courses. Undergraduates can enroll in Medieval English Literature, Renaissance Literature, Romantic Poetry, Early American Literature, Shakespeare, Beowulf and so on. Courses dedicated to Nigerian or Kenyan Literature, or single-author courses on canonical figures like Achebe, Ngũgĩ, or Djebar, or period courses on precolonial literary Africa are rarely offered. And, of course, other equally important literary traditions (Asian-American, Caribbean, Australasian, African-American, etc.) are in similarly embattled positions within literature departments. In the US, African literature often gets swapped out for African-American works in the push for diversity despite their very different literary histories.

If Africanist scholars were permitted more leeway and given more curricular space, students’ exposure to works from the continent could deepen and increase exponentially. Furthermore, giving students access to this wider range of faculty expertise would disrupt the overreliance on a handful of representative canonical writers who are themselves often opposed to having their work deployed in this way.

African Literature in Africa

Undoubtedly, African literature is taught in widely divergent ways from department to department and from country to country. Though the structures of teaching African literature within African universities are less familiar to us, based on conversations we have had with scholars currently teaching or trained on the continent, the ideological underpinnings of curricula in Africa tend to fall loosely into either a traditional or decolonial model.

At the University of Nairobi and at Makerere University in Kampala, students gain a deep knowledge of African literary traditions with emphasis placed on orature and orality. This, we surmise, is due in part to Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Henry Owuor-Anyumba and Taban lo Liyong’s efforts in 1968 to decolonize the curriculum, famously described in the subversive memo, “On the Abolition of the English Department.” Though a core text of decolonial theory, so few institutions have put its ideas into practice in the 50 years since it was conceived. Other sites where decolonizing curriculum is at the forefront of campus debates, can be found in certain South African universities: at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg which offers both a BA and MA in African Literature; at the University of Cape Town; and at Stellenbosch University.

In contrast, the second, traditional approach to teaching African literature on the continent describes the vast majority of departments that continue to prioritize Western canonical works over African ones. This Bloomian vestige of colonialism places British or French literature at the heart of literature curricula. Most universities in Cameroon, for example, and several institutions in North Africa are rigorously European in their curricula with very little focus on African or postcolonial writing. It also appears that though there are some attempts to broaden literature curricula in Nigerian universities, quite a few of our Nigerian colleagues, who form a large contingent at the African Literature Association, mention the difficulties in pushing these agendas through the system and in getting Nigerian university departments to embrace decolonized literary models.

Of course, our binary model insufficiently describes the institutional and regional variety of approaches to teaching African literature in Africa. We are aware it also does not adequately represent the curricula in local languages such as Arabic in Egypt, or Swahili in Tanzania.

Going forward

Regardless of the very clear sense that there is much institutional work to be done, the sheer number of discrete literary texts being assigned illustrates the vitality and diversity of the field, and also attests to teachers’ pedagogical commitment to refuse curricula that homogenize the continent. It is heartening to note that this survey’s results suggest that instructors are solidly committed to experimenting with decentered, non-canonical, and potentially decolonial frameworks by assigning texts that cover a wide range of histories, genres, and literary traditions.

This survey is a first step in assessing the teaching of African literature in a multitude of departments. We recognize the vastness of our field and the inherent limitations in our research methods. But this survey and our early observations are first and foremost, a provocation.

These days, the push to “decolonize the curriculum” dangerously approaches a facile tokenism we wish to resist. So-called classics continue to get prioritized but with some commentary on racism or sexism folded in. Syllabi get sprinkled with black or brown writers, women writers, and gay writers. But these gestures are nothing more than a cursory nod to diversity. This diluted approach towards decolonizing our curricula that dominates many Western universities has to stop. It is high time that institutions of higher education carved out more space and funding for the study of marginalized literatures, and reckoned with the deeply embedded epistemological biases inherent in curricular design. Individual departments must be willing to alter their definition of diversity itself, to decolonize diversity, if we may. Giving students access to the massive existing body of African literature is just the beginning.