Now is our time to tell our own stories

- Kira Bermúdez

The celebrated Mozambican writer, Mia Cuoto, argues, among others, that it is essential that governments think in terms of the nation, not its elites.

Mia Couto at Fronteiras do Pensamento, São Paulo 2014. Image credit Greg Salibian via Wikimedia Commons (CC).

- Interview by

- Tania Adam

My second encounter with the Mozambican writer Mia Couto is touched with a certain familiarity. We recognize one another right away, perhaps because being Mozambican is a code we share. I interviewed him for the first time in 2016, when he came to Barcelona to give a lecture at the Center for Contemporary Culture (CCCB) on the occasion of the exhibit, Making Africa: A Continent of Contemporary Design. Strangely enough, we have never met in Maputo. Couto has become the pride of Mozambique, very respected within the country and beyond. His literature has managed to cross the borders of the Portuguese-speaking world. His books, translated into several languages—many a translator knows it’s not easy to put his words into their language—have brought him back to Barcelona. He was chosen to be the 2019 speaker for a much-loved festival in town, which he didn’t know existed: Sant Jordi Day, an annual cultural event that celebrates literature and encourages reading. Booksellers fill the streets of the city every April 23rd with stalls and books at discount prices. In any case, being African and Mozambican, I can’t say how pleased I am that he was chosen to be the town orator at the most important literary festival in Catalonia.

A writer and biologist by profession, Mia Couto has been publishing features, stories, and novels since 1983. Back then, Mozambique was deep in the throes of civil war, a tragic destiny for those who, like him, took part in the revolution and in the struggles for liberation from colonial power. His revolutionary and dissident nature hasn’t abandoned him, but he doesn’t need to raise his fist anymore because he knows how to seduce and dissent by murmuring. His view is that great transformations are not achieved by shouting, and this is why he is one of the few outside the government in Mozambique with a voice.

Wars are thorns that pierced our young country, and his books highlight this sharpest of thorns. His characters are borne out of the pain and suffering of a hurt and resilient country, because one thing that distinguishes Mozambicans is their resilience. When I read Mia Couto, I am transported to that red earth that saw me come to life, I can smell the Mozambican breeze, and I feel the fear of the unknown coursing through my entire being. Mia connects unconnectable worlds like few know how, perhaps because the strangeness of the human condition is what comes naturally to him. He recently published his Mozambican trilogy Sands of the Emperor (2015-2017), a historical novel in three volumes: Woman of the Ashes (first of the trilogy and only volume published in English to date, by Picador in 2018), The Sword and the Spear, and The Drinker of Horizons. The trilogy is historical fiction that narrates the war waged by Portuguese colonists at the end of the 19th century against Ngungunyane, the Emperor of the Kingdom of Gaza.

It isn’t an easy job trying to find some time with him, I have to call here and there, but he finally grants me a privileged time: Sunday afternoon. I meet with him at his hotel in hopes of having a conversation about his literature. However, Mia Couto is not only a writer or a biologist; he is also one of the most lucid contemporary African thinkers of our time. Ahead of him are two days of interviews and commitments before returning to his base camp in Lisbon, where he has settled for a couple of months in order to travel from there to Brazil, Barcelona, Switzerland, the UK.

I’d like to start by talking about your Mozambican trilogy Sands of the Emperor, which was published last year in Spanish in one volume under the title of Trilogía de Mozambique. I was surprised that you chose to focus it on the figure of Emperor Ngungunyane. For me and for an entire generation, the first thing that comes to mind whenever this emperor is mentioned is the song “Ngungunyane na baliza…” We used to sing it when playing hide-and-seek. I don’t know whether kids still play the game, but we had no idea who he was.

Yes, I think they still do play the game, but I doubt they know who Ngungunyane was, even today.

This makes me think that, as Mozambicans, we don’t know our history well enough. What should we do to recover our historical memory?

To begin with we should be talking about historical memories, in the plural, because there are different memories, and my intention with this book is to show that there are different visions of the past; there’s the colonizer’s view and there’s the view of those who were colonized. What I try to portray throughout the trilogy is that the colonizers and the colonized have different perspectives. The case of Ngungunyane is peculiar; he was an African that confronted colonial rule while he himself was a colonizer. He colonized half of Mozambique to the Save River and established a relationship of domination and oppression over other groups. This ambiguous position doesn’t fit into the simplified version we are told about Africa. That’s what got me interested in narrating this story.

I suppose it’s the story of power and the people: a few colonizing the rest.

That’s right. It’s also the story of human relations; there are people who may want to colonize others. Colonial history is a reflection of authoritarian human relations, the imposition of power, the invalidation of the other, the oblivion … But with this book I’ve tried to convey that memory is ours. Now is our time to tell our own stories. So far it’s been the European colonizer who has related history.

Last November I was in Maputo for a short visit. I tried to get involved in cultural life, checking out what the city had to offer, going to bookshops, events and so on. I understood that the shortage of bookshops is a symptom of cultural poverty. Do you share this view?

Impoverishment is obvious in Maputo but I just got back from Brazil and Portugal and I have to say that, sadly enough, this is part of a global poverty. In Brazil many bookstores are closing down. The trend now is for sales of what is commercially reliable; bestsellers or self-help books. It might not be as evident in the western world as it is in Maputo, which never had more than three or four bookstores, or if there were any at all it was during colonial times, serving only the small Portuguese elite.

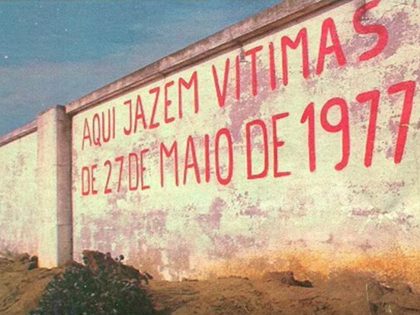

But small groups of activists and organizations are emerging that produce books and make them known. It’s important for this production to include historical memories, because we are victims of a history that says that Mozambique began on Independence Day, on June 25, 1975. This single version of history, created and disseminated by the government, has been mistaken for that of the Mozambican nation itself. This occurs because we don’t have a good archive, a memory record where you can research information and understand the present.

For instance, if we had recorded the memory of the inhabitants of Beira, the area most affected by Cyclone Idai, we would have known that there were two cyclones in 1962 and 1963, and Idai wouldn’t have caught us by surprise. We could have gone in search of the knowledge gathered by the people who experienced it at that time, before independence. Yes, an independent and sovereign country began in 1975, but it already existed as a nation long before that.

Is the erasure of this collective memory voluntary?

I don’t think it’s intentional; it’s more a genuine issue of that period. We thought the time previous to independence was a time that belonged to others. From 1975 on, we were at a new turning point that was colonized by the winning party, FRELIMO (Mozambique Liberation Front). But now we are beginning to understand that Mozambique is more diverse and complex than anyone could have thought at the start.

Who thought so at the start?

In those days we took a stand, intellectuals, academics, scientists or me as a journalist, based on the thought that we were simpler. We were contaminated by the cause, drunk on the epic idea of building a new country. The idea of homeland and nation was vibrant. In that sense, I took part along with others in the extermination of Mozambique’s indigenous languages. We thought they should only be spoken in domestic spaces, not in the public sphere. During Samora Machel’s government (1975-1986) these languages were even forbidden at schools. Today I see this as sacrilege.

So colonial values were perpetuated.

It was not intentional nor was there any evil design, but there was a fear that accepting the different languages might create a division. At that time, the understanding was that there shouldn’t be any talk of languages or races. The outcome was that languages ceased to exist, as did whites and blacks and Indians and mixed race people… Speaking about this was seen as a provocation. There was only Mozambicans; that was the narrative then. We had to build a new country.

This reminds me of the pact of silence that the writer NoViolet Bulowayo talks about with regard to many uncomfortable situations in Zimbabwe, our neighbors. Did the same happen in Mozambique?

Silence is the right term to describe what happened. When a new country is born, there is always the probability of silence, so I don’t think it’s a unique situation to Zimbabwe or Mozambique. If we look closely at the history of any nation, we’ll see that they are created through many instances of oblivion, because forgetting is necessary. Remembering is necessary, but what is remembered will be chosen. That means that whoever is in power will choose what is to be forgotten and what is to be remembered. And there’s always more to forget than to remember. In the particular case of Mozambique, we are forgetting the events that took place after independence, like the Civil War. Seventeen years after the peace treaty (1992), nobody talks about what happened during the war, it’s as if it had never occurred, and obviously that can’t be good because it’s a “false forgetfulness.”

Does this have to do with traumas?

It has to do with the diversity of voices that make up a nation. The creation of countries is done by excluding “the others,” it’s like saying “this is our chance.” This voice is repeated throughout the history of humanity.

How can these voices be transformed through literature?

The role of literature is essential because it always helps to create a nation. It contributes to building a narrative that can then be shared and studied at schools. Literature can do therapy although it’s not a solution, because it tells our history and allows for a certain catharsis and has the ability to reduce fear. Open political regimes are needed to allow for the emancipation of citizens, and that entails having a well-functioning rule of law. However, I am under the impression that we’re going through another period now, that of the authoritarian state that builds on fear and construes difference as a threat through migrations, Muslims, the “others”… I think it’s essential that governments think in terms of nations, not elites.

During my last trip I had the chance to pay a visit to the Leite Couto Foundation. What is its goal?

The foundation aims to continue the work started by my father, the poet Leite Couto, who died five years ago. His death revealed the extent of his support to Mozambican culture. He supported young anonymous people to write and publish. After his death, we received an avalanche of messages from all over the country. On the other hand, I’m used to being stopped on the streets by youngsters who want to show me their texts. So, we created the foundation to continue the task of making their work visible and giving young people opportunities, but not only in the literary field; also in painting, sculpture, music or theatre. In each area, we try to open spaces for public exhibits and this is altruistic, so we also put together exhibits with well-known artists and this allows for some income to sustain the exhibits by young talents. We do the same with books, we’ve already published fourteen books and ten of them were written by authors who had never published before and couldn’t have without help.

Must they publish in Portuguese?

They can publish in the language of their choice. Unfortunately, I know only of two authors in Mozambique who have dared to write in their mother tongue but it hasn’t worked very well since it’s not only a matter of publishing; you need a market too.

There is a market under way in Barcelona. You are here to be the speaker of the Sant Jordi Festival, you’re known as a writer here, more than in Madrid.

I’m happy to be here but I think this is not only my work. Africans have worked to open up this space. We help each other. I also wish Mozambique were more proactive about making voices known outside the country.

In our previous conversation you stated that Africans, people from Mozambique, were lost. While I was in Mozambique, the Catalan philosopher Marina Garcés published an article called “El dur treball de la cultura” (The Hard Work of Culture), where she drew attention to the importance of culture in transforming subjectivities. That idea of being lost stayed with me for a long time until I came upon her article. Then I understood that perhaps this confusion stems from the cultural deficit leading people to not know where they are from, where they are, let alone where they are going. What can be done to prevent this disorientation?

The answer is complicated; there is so much to be done that I wouldn’t know where to start. In the end, the writers, the artists… we are to blame for the commercialization of culture and for packaging it into small products. We have also accepted the definition of culture as a ghetto, as a section of the world. We should reclaim culture as a whole. Because for example, the responses to territorial claims, in Spain, Catalonia, in Mozambique, Maputo… are based on the holistic idea of culture, not as the ghetto we’ve been put into, where we’ve agreed to remain. We are not playing at writing, at making music or poetry; this is more serious. Now, more than ever before, we’ve got to integrate the holistic sense of culture by thinking of radical solutions to the problems we experience. Not everything has to be read in economic terms. It’s important that this position be held together with a guerrilla war of sorts, to alert those in power of the necessary transformations. However, this requires dialogue; we have to listen to one another, not only to those who think like we do.

These are times of stigmatization and polarization, where even those who call for inclusion are unable to engage in conversations with those who don’t share the same political ideology or because they are right-wing extremists. We need to remember that very often people join the far right not because of their political convictions but because of their fears and social threats that are falsely construed.

You always talk about fear. Actually, I just recently read an article of yours called “Fortalecer el miedo” (Strengthening Fear) which was published in La Maleta de Portbou. Why is fear so important from your standpoint?

Fear is biological; it’s an internal alert we all have in order to respond to certain dangers. Current political regimes manage fear well. We are living in a time where people can’t seem to see the future; they perceive survival based on the creation of narrow identities and are pushed towards primitive emotions like fear. They consider that survival is at stake, and that’s an impossible place from which to think as citizens and social agents. And it’s not a matter of individualism. Quite the opposite; it’s belonging to a tribe or to an army that can afford us protection but by annihilating “the other.”

The Mozambican condition has been there before. We killed one another in a civil war that lasted seventeen years. After that, we had no choice but to sit down and engage in dialogue. We sat at a table with those we considered demons and devils. In that dialogue, it was understood that we weren’t that different and we realized that what separated us was construed, invented. Fear is always more invented than it is real.

Just a few weeks ago, Mozambique was hit by Cyclone Idai, right in the area where you were born, in Beira. I’ve been following the articles in media sources that didn’t exist during previous floods, like in 2000. I mean that the scenarios of cultural representation of the African continent have changed and now there are many voices making complex analysis of the situation. There is no single voice, the voice of the savior that is also the executioner. The new voices address the issue of economic reparations for climate change. I’d like to know what you think about this position. Also, as a biologist, how do you see the present situation in Mozambique? Is the country in danger due to the consequences of climate change?

We have several answers and all of them are true, although they are contradictory. On the one hand, I believe Mozambique should take a stand as not guilty for the climate changes in the region. The culprits must pay compensation, not give aid, which is different. But this position mustn’t exempt us from taking our share of the blame. Mozambique isn’t an industrial country but it produces a lot of CO2 and greenhouse gas emissions through uncontrolled waste burning.

Each year three big cyclones hit the coast of Mozambique. This is a meteorological fact that has gotten worse because of climate change; it’s not new, nor a surprise. As I said, in 1962 I was in a cyclone in Beira, I was barely seven years old but I remember the roofs flying as I watched from my window. It was fascinating but I didn’t understand that what was happening was a tragedy. Cyclones are not exceptions, they’ve been occurring for a long time. So, we can’t keep calling this catastrophes and accidents; they are part of our meteorology. We are in a territory that must have strict response policies for these situations.

What is the role of the Mozambican state in environmental management?

Our tragedy is that we are dependent on people’s will; there are no state actions that are independent of the people. Now we have an Earth and Environment Minister in Mozambique, Celso Correia, who is making good progress on environmental issues. One of his great achievements is the restriction of logging, and many Chinese companies are starting to leave the country. He is also reclaiming the Natural Parks. My greatest satisfaction would be to see institutions grow beyond the people.

So, there are national development and environmental protection projects in place?

Yes, and there always have been, but only on paper. What we need is a commitment to implementation.

Cyclone Idai didn’t come at a good time. What consequences will it have?

Idai arrived at a time when the country’s debt is high, and the existence of a hidden debt was just recently revealed. On the other hand, we were about to start gas production, which was our hope for economic recovery. Of course Idai has hit us economically; my estimation is that we have had a ten-year setback, and it will continue to take its toll. Aid is barely available, and whatever has come our way is not enough. But this is one more African tragedy, it will be forgotten and we’ll have to deal with it on our own. Despite this terrible tragedy, work is being done to improve infrastructures in remote areas. This means there is a policy in place for building and infrastructure to improve the people’s quality of life.

So the country isn’t paralyzed.

No, not at all, we’re lucky we don’t have oil and have gas instead. Oil encourages the conditions for fast corruption and the absence of state organization. But gas requires a huge investment in infrastructure and entails the creation of small businesses in order to distribute wealth. Now our concern is that they be national businesses, not foreign.

To get back to your literature, there’s a particular view of your novels in the West regarding magic realism, African mythology. Do you think this view of your work is accurate, or is it judged as remote and exotic?

The main trend is to read my work as exotic, and that perpetuates relations with Africa which develop within the stereotyped frameworks built in the West. It’s also true that these stereotypes are perpetuated by Africans who continue to make the literature that is expected of them: with witch doctors, myths, tribes… But now there are Africans who are opposing these views and introducing other trends and styles. New generations don’t care anymore about what the West expects of them. I feel proud when I hear voices that have risen out of the African ghetto and engage in a dialogue with the world.

What role do young people have in the future? Although you claim that the idea of future doesn’t exist in African languages.

Yes, but people have the idea of future in mind. Perhaps we should make a distinction between what goes on in rural areas and in the city. For rural peoples the idea of future is what occurs within their own horizon, their sense of the village like a country. Although their perception is changing as mobile phones and the internet broadens their understanding of the world. In contrast, urban youngsters are more demanding, they are no longer satisfied with a political discourse steeped in colonialism and blaming Europe. They want to see transformations and act to achieve them, and I am so happy to see so many cultural and community organizations being created. In Luanda (Angola), for instance, cultural vibrancy is so interesting. This change in mindset is very important because they understand that they don’t need to be sitting around waiting on the state. I often wonder whether there should be state intervention in cultural affairs.

Well, I think each has a role to play. I guess we have to find the right balance for state cultural intervention. We should avoid what happened in Spain, where there was excessive cultural intervention until the crisis hit and then they didn’t hesitate to cut budgets. I’m so happy to see that civil society is carrying the greatest weight in culture in African countries although I think there should be a bit more state intervention.

Yes, I agree there must be regulations in terms of laws, but the state can’t be a cultural agent like the rest but rather a mediator. Civil society got tired of waiting on the state and is finding its own strategies for self-management. For instance, African musicians are finding their own survival strategies, while creating connections with other countries.

So relations with neighboring countries are common on a cultural level.

Not that much, really. I wouldn’t trust that Mozambicans know the writer NoViolet Bulawayo, but beyond that, they might be familiar with her although I doubt they’ll read any of her books because they aren’t translated. And if they are, that’ll be in Brazil or Portugal. So, if a Mozambican wants to know a writer from Zimbabwe, they’ll have to come to Europe. What I mean by that is that colonial relations persist. They have to come to the West to understand what’s happening in African literatures. I myself on this trip am looking forward to buying several authors’ books.

Which ones?

I read a lot of philosophy. As a writer, I’m interested in understanding how thought mechanisms are built through stories. And the Ghanaian philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah is really good in this sense. I recommend reading In My Father’s House or The Lies that Bind.

What other writers of African descent would you recommend?

There is a whole generation of Diaspora Nigerians who publish particularly in the United States; these are a world apart but they are interesting, like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who is becoming quite an institution. I recommend Chinua Achebe; it’s such a mistake that they haven’t granted him the Nobel Prize in Literature; he was a great writer of great literary quality. Women are taking strong positions; I am more familiar with those who have been translated into Portuguese, because I prefer to read literature in Portuguese. I was very pleasantly surprised by The Joys of Motherhood by the Nigerian writer Buchi Emecheta, as well as by the Ghanaian author Taiye Selasie.

You just got back from Brazil. What do you think about the situation in the country?

It’s a sick country. I see that people don’t have answers for what’s happening; they’re still in a state of shock. There’s such a sense of desolation that people even break into tears when they talk about the situation. I consider myself a leftist but I see how the mistakes of the left have helped the far right in gaining positions. From Mozambique I watched the rise of Bolsonaro and right-wing polarization while the left was worried about identity issues or cultural appropriation. For me, these are necessary issues but they’re not the big issues. Proof of this is that there’s a far-right government in Brazil now, and the people are broken.

For example, when we talk about the Négritude movements, my impression is that importing the African American perspective on race distorted the internal struggles that were related. Métissage or mixed race has disappeared. That means that whoever isn’t white automatically becomes black. Before, Brazil understood its racial complexity as a result of the country’s history; as soon as they imported the US perspective on race it turned into a victory for the far right.

How does that happen?

Because the race issue gets racialized. That is, it’s racism that produces race, not the other way around. And this principle must be understood in order to take it on. On the other hand, appealing to radical transformation by means of seduction is a must. Seduction can be as firm as accusation; it allows you to say what you must without shouting. The most important things in the world are said by murmuring, in a quiet voice. I think a false radicalization of a problem has been created by importing this idea from the United States. There, for example, if you have a distant ancestor who was black, you are considered black, but it doesn’t work the other way around. If you have a white ancestor, you’re not necessarily considered white. This idea is terribly racist, because it means it’s black blood that stains. These categories mobilize rage and hope very easily while also encouraging blind violence, blind conviction of ideas to defend. We have to understand that many mistakes are committed in a revolution. I myself was a revolutionary, and I made mistakes because I didn’t see them, I was locked up in my own certainty.

Can the revolution be fought through dialogue, or is it precisely the lack of dialogue that distinguishes revolution? Because if the goal is transformation at all costs, I understand there is no mediation, and soldiers are needed.

Yes, in revolutions there has to be a time when you break away from what there was. For example, when you cut a baby’s umbilical cord this is a violent and revolutionary act. We can’t imagine the violence involved in the birth of a baby, but it has to occur for life to exist. I understand that in the end you have to combine instances when rupture is needed with instances of dialogue.

But in the end we cling to our certainties because we’re afraid of getting lost. Precisely, Africans have an ability that we’ve developed that doesn’t exist in the West, and that’s the ability to embrace the complexity of life. This is closely related to African religiousness, which allows for this expansion. We don’t come from the monotheist thought system that claims to be in possession of the one and only truth; we have the ability to listen to different voices.