Pan-Africanism and the African artist

Meleko Mokgosi’s multimedia works offer complex views of history and powerful critiques of pan-Africanism and the postcolonial moment we are currently living.

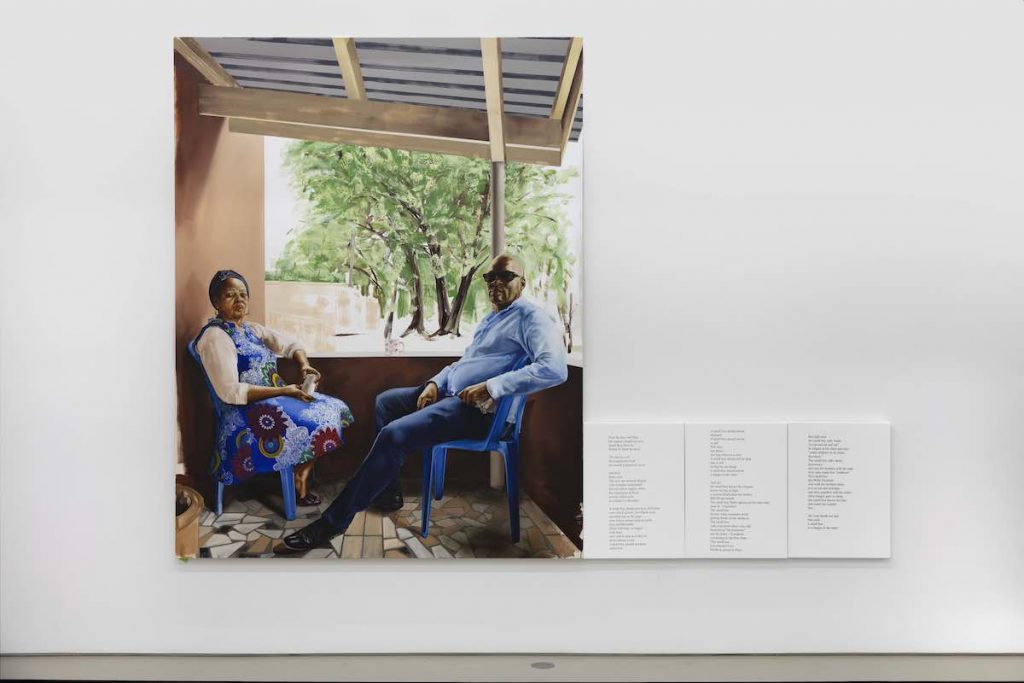

Meleko Mokgosi. Image courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery.

- Interview by

- Drew Thompson

The Botswana artist Meleko Mokgosi opened two exhibitions in early November of this year, at Jack Shainman’s New York City galleries, The social revolution of our time cannot take its poetry from the past put only from the poetry of the future and Pan-African Pulp. Democratic Intuition another multi-year and multimedia exhibition is on view until Spring 2020 at Jack Shainmen’s The School located in Kinderhook, New York. These shows are impressive for their scale and scope, and come on the heels of exhibitions in Johannesburg, South Africa at the Stevenson Gallery and at the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor.

The opening of Mokgosi’s New York City shows presented an opportunity for me to speak to the artist, who I know from our shared time as art majors at Williams College, about his educational and professional trajectory. Born in Francistown, Botswana, Mokgosi currently teaches painting at the Yale University’s famed School of Art, where luminaries like Kehinde Wiley, Barkley Hendricks, Howardena Pindell, and Wengechi Mutu amongst many other black artists have trained. Ironically, Yale and other top MFA programs had rejected Mokgosi, who after the Whitney Independent Study Program trained with the artist Mary Kelly at the University of California-Los Angeles. Mokgosi’s multimedia works take years to produce and unfold for the public in various iterations and chapters, thereby offering complex views of history and powerful critiques of pan-Africanism and the postcolonial moment we are currently living.

How do you think of yourself in relation to the history of art in Botswana? Do you have any artistic influences?

The way I got into the fine arts was having drawn for a long time, copying comics, copying stuff from the newspapers [and] magazines, and just kind of randomly. It was just through a high school teacher, who was a British artist and had been in Botswana for like 25 years. I was introduced to art basically through like Weimar Republic, German Expressionism. There wasn’t any African art [in Botswana]. There was no South African art, which would have made sense. We [Botswana] share a border with South Africa[, and] we share a close history with it. I did not know any of those people, whether like William Kentridge. So, it was kind of a precarious and weird thing. But I guess it is just the baggage that we have as we developed.

That came with the colonial institution or the legacy of education in Botswana?

[T]he education system [in Botswana] for a long time has been based on the Cambridge education system. I read Jane Austen through and through. That kind of work took me to English literature. Actually, at Williams College I focused more on English literature than like painting. So even without the fine arts, the cultural production was British oriented. I was just speaking to someone in Chicago who was organizing a really amazing exhibition around Medu [Art Ensemble], a poster collective. I met a curator at the Art Institute of Chicago, Felicia Mings, and one of the questions she asked, “Did you know of this thing [MEDU Art Ensemble]?” I was like “No.” Even if I was to go back home, no one knows what MEDU is. No one knows the connection them starting in South Africa, moving to Botswana, and still producing these really important cultural artifacts. I guess it is the same thing with the Pan-African Pulp stuff. Not many people know them. Like, no one knows a lot about it in Southern Africa.

You talk of yourself as this artist of the West who could be from Botswana. Could you talk about your educational trajectory as an artist?

My approach, which again comes from this very peculiar entry through German Expressionism, was the idea of the artist as someone, who first and foremost invested in a kind of socio-political engagement with the contemporary. People like Max Beckmann and Kathy Kollwitz were engaged with the questions of the day, which had to do with fascism and the working class, a kind of specific inequities and inequalities, and also with pedagogy. They were interested in a public dialogue in a critical setting. That’s what being a painter meant. Going to Williams College really was an important step for me. I came in with very specific tools of painting. Then I was taking classes with Ed Epping, Laylah Ali, and Mike Glier, really building the conceptual tools. It really was not so much fine tuning the painting. It was kind of building that conceptual framework under which I wanted to make these statements.

But we might want to add that Ed Epping, Laylah Ali, and Mike Glier, were all drawers at their core?

Totally. I had to paint in that way [of drawing]. I drew in charcoal for seven or eight years. Until 2003, again, this high school teacher, after a while he was my mentor, he brought me some paint. You look at how I paint, then it looks like I use paint as if I am drawing with charcoal. Charcoal is very reductive. You put down pigment and you remove it to the volume, and so forth. That is literally how I paint. I don’t paint in terms of additive formulations. It is more subtractive, basically. It was really amazing to go there [Williams]. The art history made me aware of it, the history. But, then again, I was really narrow. I left Williams without knowing any African artists, any African art history. It was mainly Europe and America, you know. But, it actually prepared me to go to the Whitney Independent Study Program. Because I think without that strong foundation of history and [a] conceptual [framework], I don’t think I would have been able to fit in, be accepted into the Whitney Program. It was there, always political, always trying to figure out what I was trying to do. And at the Whitney was also a big game changer. I was forced to think about the natural language of painting. This was also where I met Mary Kelly, and this was where I was like it was not about painting.

It is an interesting point you make about your trajectory and schooling in art. It seems to me your practice is about unschooling, reschooling on certain concepts that have been formative to your life as well as to the cannon. Who do you envision as the audience of your work?

I guess it depends. The paintings, like if someone is from Maun, which is where I am from, [my paintings] would make sense at a certain level. They can identify with the kind of texture and the kind of atmosphere. But, they wouldn’t need postcolonial theory to unpack it. There is a certain identification that comes with it. Whereas in academic contexts, someone might not be able to identify with this history or context but they might be able to identify with the discursive framework, which [relates to] a certain kind of critique of art history, a critique of representation, postcolonial theory, critical theory, and so forth. So, as far as the audience is concerned, the most important thing for me is for the viewer to acknowledge and reconcile an intense amount of investment [that they] have in the things that are being represented.

A lot of work is going into institutions, which until 2003 you had never visited before. What is it, that having institutions collect this work and it being in institutions, that you hope that work will allow institutions to do?

I think again, at the basic level, is for the viewer to see that there is an intense amount of investment in these things that do not occupy the center, that are not a part of the West [and] not part of the grand narrative. The center does not matter that much. I think that is a very important part as someone who is kind of Westernized, that tries to antagonize the idea of being from the diaspora. You know I think of myself as very much from Botswana and not of the diaspora. Having worked so much to convince people that I am like them, that I am Western, that I know English, that I went to the right school, that I am part of the institution of art. There is a certain way in which when you are not from the West, you try to make yourself legible to the West in some way. I have done that in a personal way but not through the art work. That is where I draw the line. The artwork tries to make the argument that is it possible for the Western viewer, or any kind of viewer, to look at these things and find a way to abstract themselves outside of their one subject position and find a way to empathize with another subject position that does not occupy the grand narrative. Again, engage with this material with the recognition that they are going to fail at some point.

How much do you take into consideration the history of the people that you are trying to portray in relation to the question of scale?

It is all about [scale]; it is a way of monumentalizing and bringing into center things that have not been allowed to occupy certain space. [H]istory painting [is] a way to communicate very specific kinds of historical events of very monumental people. So, I am using that scale. But then inserted in the idea of cinema, which is why the work tries to mimic the film strip, as a way of building an installation that allows the viewer to enter it and become a part of it and to engage with it. And also, the idea of genre painting, the idea of a Dutch trope, the mundane quotidian space, where someone made doing something. In a kind of art historical context, the genre painting was kind of the ordinary thing. So, I am mixing these tropes to kind of produce representation. Also, I think scale has to have a 1:1 relations. In cinema, it is important to think about the kinds of shots you are using. So, I don’t use any long shots or close-ups because those have very specific kinds of functions. I use a medium shot, which allows a certain amount of context. The long shot is about the contextual thing. I am not interested in that. I am not interested in saying these are the facts; these are the things I am talking about. I am always skeptical of the idea of history.

What has the use of photography taught you about your painterly technique? How have you used photography to rethink painting as a mode of representation?

I do work mostly from photography, pretty much exclusively. Half from pictures I take and half from appropriated images. I would say it [photography] is more limiting than I found, not just for myself. But, if you look at painting in general, in the last 150 years, it is very much tied to the pictorial framework about the picture, about how photography captures space. It is something that I am trying to overcome now. I am trying to figure out how to expect space, how to think about space differently, how to think about things like the pose, setting, lighting—these things tied to the photographic context. But, I have pretty much painted with that kind of mechanism. But, it is also a way to relate to the history of representation, which, if we think of the black African subject, that subject enters the visual language of West through an ethnographic and anthropological framework. Again, that is an important part I tried to think of: What kinds of images have been reproduced and what politics do these images reproduce?

You give space in your paintings to your photographs. In this exhibit, I see Winnie Mandela and Hollywood stars.

How photography functions in the Southern African context in general is very much tied to liberation struggle. Especially if you look at South African photography, a lot of the precursor to a lot of South African contemporary artists, mostly photographers.

You could say that as well of Mozambique?

People weren’t sitting around painting. People weren’t doing installations. Photography was a medium of communicating struggle and trying to get the word out there, that is what was happening or these were the politics, domestic servants and mine workers. That only exists in a documentarian historical context, unless someone like Ernest Cole is known in the art context. Then again, he is more well known as someone who has documented the apartheid regime more than a fine arts photographer. It is important to fold in these other forms of representation, that have to do with someone like Albertina Sisulu or Winnie Mandela, who are important figures in the struggle, [and] to do so in painting in the form of photographic representation.

It also shows how photographs inhabited people’s lives. They [the photographs you reproduce] were the images they saw every day?

Absolutely, these are all things we lived with. That’s why I use a lot of posters. They are objects and images that we lived with. They fed our imagination and tried to get us to conceptualize things differently.

Pan-Africanism and nationalism embodies your work. Sometimes, I saw your scenes and thought they could be of anywhere in Africa. But, as we know, the pan-African vision was not kind to everyone in Southern African. Botswana inhabited a very different geography when it came to pan-Africanism and apartheid.

Well, Botswana was not touched by those things. Again, it depends. Most of the images I deal with mostly happen in Botswana or South Africa. Because, I think there is a certain kind of physiognomic difference when you look at people from like Mozambique, who are of Portuguese heritage. People have different kinds of heritage. That’s part of my politics. I don’t think I can speak from subject positions that I don’t know anything about. Maybe that why it is hard for me to paint things about African-Americans. I don’t think it’s my place. I don’t want to enter those politics, apart from that painting based on the Aaron Siskind photograph. The pan-African part has molded with the new project, the new kind of desire to try and overcome the limitations that have been put in terms of the idealization of pan-Africanism as a political strategy and also as a patriarchal structure from 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, and so forth. To kind of figure out it’s more personal, as well as political, continuously trying to reconcile my position in the American context as someone who does not identify as black. But, I identify as African. The American historical context is very invested in interpolating my subject position as a black subject, and [I’m] having to deal with that modification that I am black.

Then there is the diaspora framework?

Totally. I had to come to this country [the United States] to experience my blackness in a certain way, which I am trying to reconcile with. And, I am trying to do it through this thing of pan-Africanism, as very naively my understanding [is], trying to use it as a political strategy that is sustainable, as a way of fighting white supremacy.

How much does titling the work, as well as the way you use color factor into that approach of pan-Africanism and wanting to rethink [your] positionality?

I had to unlearn academic painting to formulate another way of painting, the black subject as a way of engaging with the history of representation [and] of not using white or academic formulas, again white, magenta, green, and blue. But, you know I basically had to come up with a concoction of painting flesh tones in a way that capture the likeness of the black skin. And, I think that is a part of the politics. The instruments that you use to communicate should also be part of the content. I think in art historical frameworks people tend to think of the content and technique separately and actually it is not. The tool is very much a political gesture. The same with the titling. I usually never start a project without the title.

With pan-Africanism, I am trying to figure out how blackness manifests in specific contexts. If you look at Kerry James Marshall, the way he is thinking about blackness is very specific. He uses color in a very particular and political way. He also uses acrylic paint not oil. He uses highlights. I would make the same argument of how I use paint to try to engage with a certain kind of blackness, which is, in the Kerry James Marshall case, blackness circumscribed in the discourse of whiteness and the limitations that [representation] has put on access to the black historical subject in that cannon. Whereas, I would say that the way I am thinking about blackness has nothing to do with race discourse; it is much wider I would say. It is related to the colonial discourse, which is about a certain kind of whiteness. It is not whiteness that has to be in blackness.

I think the idea of blackness in the West, and in the art historical narrative, is really narrow. I think it is so narrow that it is actually kind of violent, because there is only one kind of blackness that is legible and that is African-American blackness. There is no other kind of blackness, African blackness, South African blackness, Brazilian blackness, Australian blackness, blackness in Eastern Europe. I am thankful the African American blackness is at least visible and that there is a certain kind of gesture towards it. There is a certain kind of hope for the kinds of blackness that we want to deal with, that they might be legible at some point.