Black African immigrants, race and police brutality in America

Most poor African immigrants to the US can't pull the “get out of black”-card when confronted with racism, something middle class Africans can pull.

Image courtesy of Glenna Gordon.

Perhaps the most famous example of “African passing” is the infamous anecdote of former UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan. A student in 1960s U.S., Annan had traveled to the Jim Crow South. He needed a haircut, but was told by a racist white barber: “I do not cut nigger hair.” Annan, who is Ghanaian, responded: “I am not a nigger, I am an African.” In doing this, Annan did not challenge the degradation pre-assigned to him by virtue of his skin color, and accepted the premise that there is something inherently pathological about American blackness to which black people from Africa are impervious.

This line of thought is not uncommon. As Chimamanda Adichie, herself a Nigerian immigrant to the U.S., has stated: “When you’re an immigrant and you come to this country, it’s very easy to internalize the mainstream ideas. It’s easy, for example, to think, ‘Oh, the ghettos are full of black people because they’re just lazy and they like to live in the ghettos.’”

The evidence put forth by the characters that showed up from America on our living room TV in Tema, in Ghana where I spent my early life, seemed bent on conveying that black people were a problematic sect in the United States. Whether from CNN’s discussion of crime and violence, or in the rap videos buoyed by the twin manifesto of brute force and wealth, this perennial drip feeding meant that even before our plane had taken of from Accra and headed to JFK, I’d be admonished by extended family, pastors, market women and an air hostess – none of whom had lived in America – to not become like “those black people,” the Akata people.

The problem of such marching orders is that in America the definition of blackness – with its complex history – often lies in the eye of the beholder. It is as the truth for many Africans, as the novelist Yaa Gyasi wrote, that “when my little brother had the police called on him by our new neighbors while riding his bike on a nearby lot, he couldn’t say to those officers, ‘It’s O.K., I’m Ghanaian-American’.”

Unlike in Kofi Annan’s (problematic) case, most Africans – particularly poorer immigrants – don’t get a “get out of black free” card in instances of race prejudice. It wasn’t the case when four plainclothes officers shot Amadou Diallo (an immigrant from Guinea in West Africa) 41 times, as he pulled out his wallet in 1999. Seventeen years later we are again suffering with the tasering, shooting and summary killing of Ugandan immigrant, Alfred Olango, in San Diego. What these acts of police violence show is that the desire to self segregate in matters of race prejudice is indulging in a fantasy.

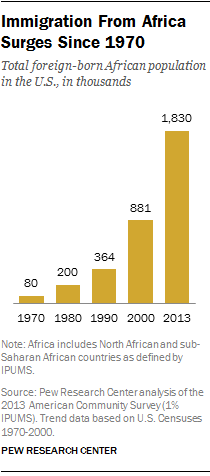

The fantasy may derive from a superiority complex. As Pew research shows, there are more African immigrants with college degrees relative to the overall U.S. population. But respectability or the lack thereof is no reason for someone to die, no matter their race. What matters is that the black immigrant population has grown by 137 percent in the last decade, and forms a relatively larger percentage of the overall U.S. black population. In America these days, Africans are the new blacks. Studies show that by the second generation many black immigrants lose the cadences and other linguistic signs that their parents still maintain. Children leave the tightknit community to go to college, and families in general disperse around the country in search of education and better opportunities, melting into the general black experience in America. Whatever challenges stand in the way of black individuals and families in the U.S.are our prerogatives.

Consider, for instance, the revelation from the National Academy of Sciences’ report on the integration of immigrants into American society. The finding show that black immigrants are “more likely to be poor than the native-born, even though their labor force participation rates are higher and they work longer hours on average.” Although the poverty rate for foreign-born persons in general declined over generations to match the native born, poverty levels among black immigrants rose to match that of the native black population.

Since black immigrants make up a double-digit share of the overall black population in some of the largest metro areas for instance, we have to accept the fact that African immigrants will be victims of the larger epidemic of gun violence that has disproportionately targeted people of color in America. Another tragic aspect of Olango’s case is the fact that he was a refugee. But that is hardly unique; about one-third of immigrants from Africa enter the U.S. as refugees. In Olango’s case, he had had fled his hometown Koch Goma, living briefly in Gulu before traveling to the United States in 1991.

So, you can imagine the extra pain of toiling, through persecution, surviving through camps, making the journey here and putting up with all of the challenges of adapting to a new society and culture in order to construct a home for your family only to have all of that sacrifice and work annulled by the lack of self control or training of an American policeman. As Agnes Hassan, a Sudanese refugee who had been in a camp with Olango asked “We suffer too much with the war in Africa, we come here also to suffer again?”

I remember very vividly, the late afternoon of December 13th 2014 at the Justice for All March in D.C. when Amadou Diallo’s mother, Kadiatou Diallo, said from the stage: “This sorority of sisters, we the moms, we don’t want to belong to this group. We’ve paid a heavy price to be here.” The sombre statement struck my heart, but it was her accent, reminding me of my mother, which was dispiriting and discomforting. It really could have been my mother up there at that moment.

We minimize the power and stake that African immigrants have in the conversation about racism when we forget it was the case of Amadou Diallo, an African, that was one of the first to mobilize protesters and demonstrations against police brutality on a large scale; and in a city like New York nonetheless. Since then we have protested the killings of Sudanese Jonathan Deng, Cameroonian Charley Keunang or Deng Manyoun in Kentucky among myriad cases that we don’t know about because they didn’t trend as popular hashtags post mortem, or they were struggling refugees with no extended family to advocate for them in life.

It can be tempting to want to compare police brutality here to violence back home, as the Nigerian author Adaobi Nwaubani did, when she told PRI after the first presidential debate “I don’t want black people, or white people or whomever to be shot and killed in interactions with the police [in the US], but I can’t pretend that I’m horrified by the fact that the police stopped and searched someone.” This, however, overlooks centuries of targeting and persecution of black people in the country’s history. (Nwaubani, incidentally, also told PR “stop and frisk” does not strike many Nigerians as remarkable.)

As the report from the UN expert group on People of African Descent puts it, “contemporary police killings and the trauma it creates are reminiscent of the racial terror lynching of the past. Impunity for state violence has resulted in the current human rights crisis and must be addressed as a matter of urgency.” Note US Supreme Court Justice, Justice Sotomayor’s suggestion that the “way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to speak openly and candidly on the subject of race, and to apply the Constitution with eyes open to the unfortunate effects of centuries of racial discrimination.”

How would Alfred Olango have known before he texted his friend Steven Ojok back in Kampala on Sunday “you know what, man, I am taking my daughter for dinner”, that there was a coffin with his name on it.