Egypt’s Modern Pharaohs

Except for one-year, when Mohamed Morsi was President, modern Egypt has only been ruled by military regimes

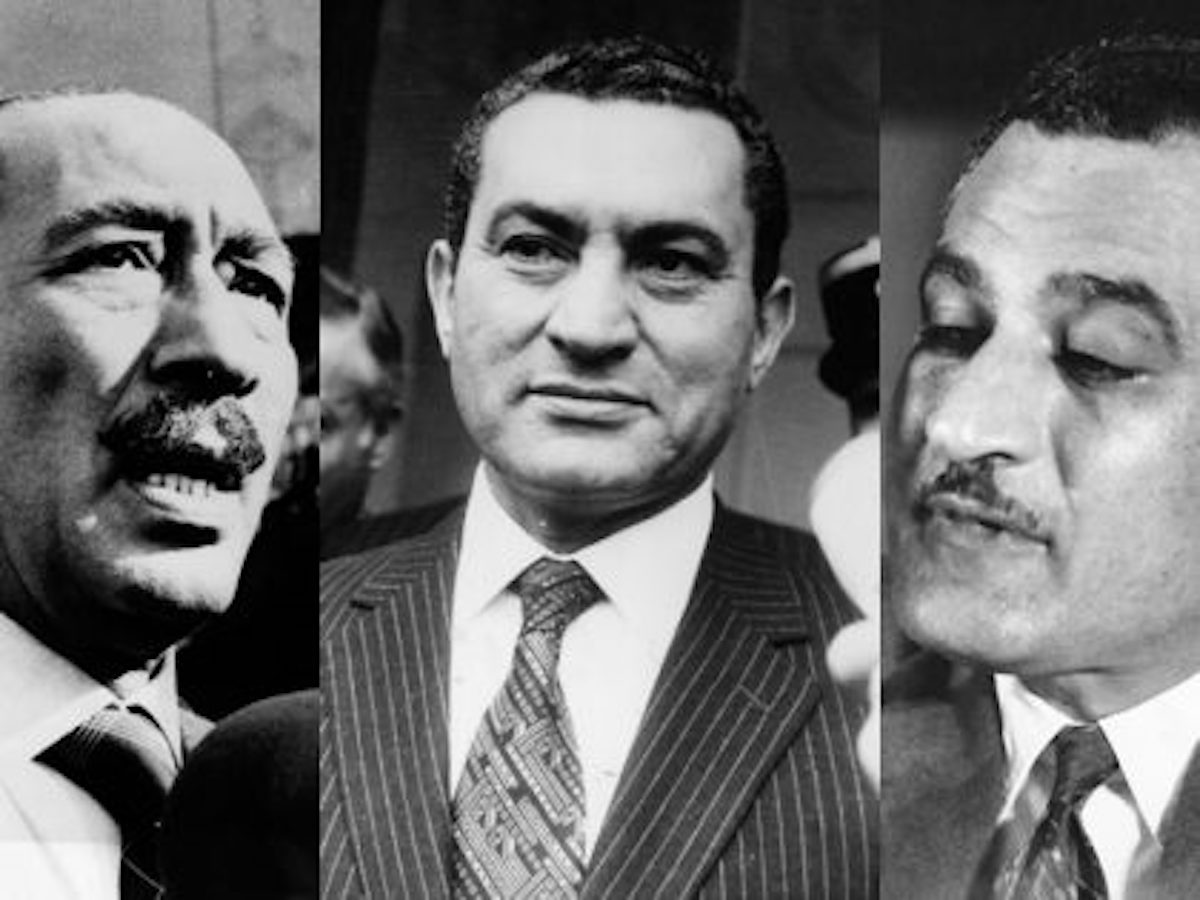

Except for a brief one-year interlude from June 2012 to July 2013—when Mohamed Morsi was President—modern Egypt has been ruled by military regimes. It began with Gamal Abdel Nasser (1956-1970), who came to power through a military coup. Nasser was succeeded by Anwar al Sadat (1970-1981) at Nasser’s death. When Sadat was assassinated, his deputy Hosni Mubarak took over until the protests of January 2011. When Morsi — Egypt’s first and only democratically elected President — was deposed, another General, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, took power. Sisi, who is currently Egypt’s President, declared in February 2015 that the country’s democratic transition “is complete.”

In a way, Egypt’s military dictators came to resemble its pharaohs, with their highly centralized governments, the creation of a culture of fear, and a cult of personality. In modern Egypt, the portrait of the president hangs in every government office, on billboards throughout the cities and on the sides of roads. Buildings and neighborhood are named for them.

Egyptian filmmaker Jihan el Tahri explores this recent history in a new, three part documentary series, Egypt’s Modern Pharaohs (link to the trailer). The series has been screened on the BBC, Arte and at major film festivals. Each part focuses separately on the Nasser, Sadat and Mubarak regimes, who combined ruled Egypt for over 50 years.

The series begins with the accession of Nasser through his coordination of coup by “Free Officers” in 1952 against King Farouk. Nasser, however, did not become Egypt’s first republican president. That honor went to Muhammad Naguib, who was born in Sudan. Within one year Nasser, using his popularity, plotted against Naguib, imprisoning him as well as, subsequently, erasing all traces of Naguib’s contributions to the revolution from public memory.

Sadat, who served as Nasser’s vice president, used his time at the helm to undo much of what Nasser had built. Nasser worked hard to unite much of the Arab world under his leadership — he is credited as the father of Pan-Arabism– but also remembered involving Egypt in costly and disastrous wars in Yemen and with Israel.

Under Sadat, Egypt signed a peace deal with Israel (Sadat visited Israel and spoke in the Israeli parliament, the Knesset) that isolated Egypt politically for at least decade. Sadat also negotiated with the West and opened up the Egyptian economy to western investment.

Hosni Mubarak took up where Sadat left off in his devotion to capitalism and western, especially U.S., political influence. The 30-year rule of Mubarak was defined by the growth of income inequalities and dismantling of the social safety nets that Nasser had put in place. Corruption ran wild throughout the country and the military consolidated its stake over the economy. The only state sector that functioned effectively, was the security apparatus. Forced disappearances, human rights abuses, and extreme police brutality were all widespread during the Mubarak regime.

One aspect of military rule that has remained relatively unexplored until recently, is its relationship to political Islam, which has always garnered large followings of devoted members among ordinary Egyptians. The Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist groups have been in and around Egyptian politics since the early 1920s and the government’s best efforts to weaken them notwithstanding, they always reemerged stronger.

Publicly, Egypt’s military regimes play up their opposition to Islamists, but enjoyed symbiotic relationships between successive Egyptian governments and Islamist groups. In Egypt’s Modern Pharaohs, El Tahri explores this rarely acknowledged mutually beneficial relationship.

Nasser, for example, exploited his relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood to gather popular support for the 1952 coup. Once he had stabilized his dominance over Egypt, he criminalized and imprisoned Muslim Brothers, including prominent Islamic theorist Sayyid Qutb. Sadat eased the grip on political Islam and actively encouraged Wahabism. Sadat’s strategy was to co-opt them so as to neutralize radical Islamists. However, the Islamists would eventually assassinate Sadat. The Mubarak regime then changed course and cracked down on political Islam. Mubarak later changed his mind and allowed the Muslim Brotherhood to participate in parliamentary elections in the early 2000s as independent candidates. The Brothers won several seats and provided a serious opposition to the ruling National Democratic Party.

El Tahri manages to interview all of the major players that were part of the drama of the last 50 years of Egyptian politics. Embers of the ruling party, the Free Officer Movement, 1970s student leaders and leaders of Islamist groups, all get their turn on camera. It’s rare to hear such candor about Egyptian political history and the film does a great job of situating the viewer into the political culture of the time.

My family is Egyptian — my parents migrated to the United States in the early 1980s — and I was brought up with the idea that these central figures in modern Egypt were infallible men of honor and patriotism. This series destroys that illusion. Instead they were characterized by political failure, deceit, corruption and greed.

To get her viewpoint across, El Tahri uses traditional storytelling techniques. At the center of the film are interviews mixed with found footage of historical significance. To add cultural depth to the narrative, she complements these with clips from classic Egyptian films and television shows that depict significant events in history. This is of course vintage El Tahri, whose films add up to an alternative history of “Third Worldism” (see for example her brilliant films on Cuba’s African solidarity campaigns or post-apartheid South African politics).

Egypt’s Modern Pharaohs was funded by a grant through the Doha Film Institute (DFI) in Qatar. Headed by Sheikha Al-Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani, the sister of Qatar’s ruling Emir, DFI is another tool of Qatar’s soft power in the region, which includes the Qatar Foundation, hosting the 2022 World Cup or welcoming many global political and economic summits. Through funding and influence in media, arts, sports, and education, Qatar has worked hard to elevate its political status in the Middle East and globally. Qatar was also a vocal supporter of the Arab Spring. As a result, the military and nationalists in Egypt accuse Qatar of aiding the Brotherhood. After President Morsi was overthrown, Egyptian relations with Qatar deteriorated, with the generals preferring Qatar’s rival Saudi Arabia. The Egyptian military viewed the local bureau of the Qatari public diplomacy broadcaster Al Jazeera as a fifth column for Morsi and the Brotherhood. After he came to power, Sisi closed down Al Jazeera’s office and jailed some of its reporters. Within Egypt, where conspiracy theories are commonplace, the sponsorship of El Tahri’s film by a Qatari foundation will thus arouse suspicion and debate, but that is a red herring. The film has to be judged on its merits.