Can the Somali Speak?

The hashtag #CadaanStudies put the spotlight on the domination of Somali Studies by whites scholars.

Stuart Price via AU UN IST Flickr.

When Oxford anthropologist I.M Lewis arrived in British Somaliland in 1955 for fieldwork that would lead to the foundational texts of Somali Studies, he did so with support of the British Somaliland Protectorate administration and a fellowship from the Colonial Social Science Research Council. It’s a familiar story across African Studies — the broader academic field to which Somali Studies belongs — and the discipline of anthropology, and an anecdote which captures the world in which anthropology and Somali Studies emerged: the European colonial encounter with the African, and the twinning of academic knowledge production with the colonial project. Inextricably linked to the new regimes of control and power governing the Somali territories were its new social scientist experts, meticulously documenting every aspect of Somali life. The production of cultural and historical information about Somalis was tied to the expansion of European power.

While recent decades have seen more and more Somali social scientists, knowledge production about Somalis remains largely in the hands of European and American academics. It’s a field that has never subjected itself to the self-critique and self-reflection anthropology was forced to do when confronted by its colonial heritage in a postcolonial world. It has not rethought the ways in which colonial dynamics reinscribe themselves in non-Somali scholarship on Somalia, nor has it critically interrogated the power dynamics embedded in the Western researcher’s position vis a vis his Somali subject. It has not questioned its overwhelming whiteness, and at its most violent, marginalized contributions of Somali scholars and writers and rendered them invisible.

Earlier this week, an academic journal was brought to my attention: the Somaliland Journal of African Studies, which published its inaugural issue in February. It describes itself as a journal “covering African affairs at large, but with a particular focus on East Africa and the Horn” and “put together with students at scholars of the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies of the University of Hargeisa.” Missing from the journal’s editorial board, board of advisors, and authors were said Somali students and scholars. Not one Somali from outside of UofH, either. Instead, the editorial and advisory boards were made up of nine European and US based academics (as well as two PhD student editors) and three Ethiopian academics affiliated with Addis Ababa University.

On my Facebook page, I called for a Twitter conversation on March 25th under the hashtag #CadaanStudies:

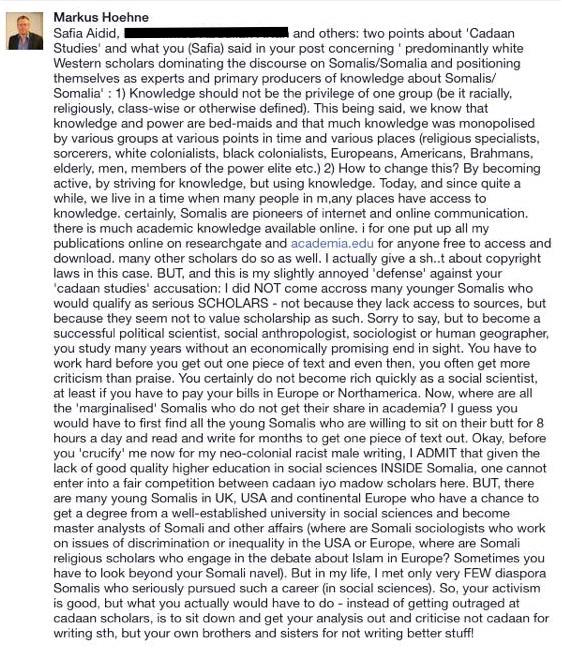

As a public post shared widely, many Somalis participated in the Facebook thread to critique the journal. The tone shifted completely when one of SJAS’ advisory board members, German anthropologist Markus Hoehne, entered the thread with comments so patronizing many of us were left wondering if we had encountered a real-life early 20th century anthropologist caricature. His defense of SJAS and “cadaan” domination of Somali Studies: Somali social scientists do not exist, and non-Somali academics will continue to dominate the field until you Somalis dislodge us:

The back-and-forth on Facebook between Hoehne and over 30 educated young Somalis ended spectacularly when he was asked to leave the thread, and responded in broken Somali translating to: “Fine, I will go. You and your friends can talk about a stupid white man who is colonizing you, but I think that when you are finished talking about colonialism, you will go back to your Somali tribalism.” His words only proved the point of the critique of SJAS, knowledge production about Somalis and whiteness, and at 6pm, we hit Twitter.

https://twitter.com/gabarnimo/status/580855213290033152

Somalis have endured 4 colonial powers, cold war, civil war, neocolonialism.But the violence of Western 'experts' harm us too #CadaanStudies

— safia aidid (@SafiaA) March 25, 2015

An academic journal on somalis with no somalis: the same colonial logic of only the whites know best how to use ideas. #CadaanStudies

— BDF (Black diaspora faggotry) (@blacklikewho) March 25, 2015

https://twitter.com/basilfarooqi/status/580860025079521280

When an East African panel looks like this #Experts #CadaanStudies pic.twitter.com/Dl5O0dnyIc

— e (@itselhan) March 25, 2015

Too busy pirating & joining al-shabab to be involved in academic discourse re our country, history & culture. Please save us #CadaanStudies

— Huda Hassan (@_hudahassan) March 25, 2015

The new face of cultural imperialism. It kind of looks like the old face but what do I know. #CadaanStudies pic.twitter.com/HXIAHA3ypg

— Mo. Ali (@MuzzleMad) March 26, 2015

My prof published a book that argued British colonial policy in Somaliland was perfect for the warlike Somali nature #CadaanStudies

— Surer Mohamed (@surermohamed) March 26, 2015

The day an cadaan PhD student wanted to document the death of my dying mother and subsequent burial because it was exotic #CadaanStudies

— Fadumo Qasim Dayib (@fqdayib) March 26, 2015

Days later, the hashtag is still going strong. As for Markus Hoehne? He had a few words to add on another Somali Facebook page following the hashtag conversation:

![]()

We have responded with an open letter.