When Salazar met one of Lumumba’s murderers

António Oliveira Salazar founded Portugal’s New State dictatorship in 1933. Some Portuguese still remember him fondly.

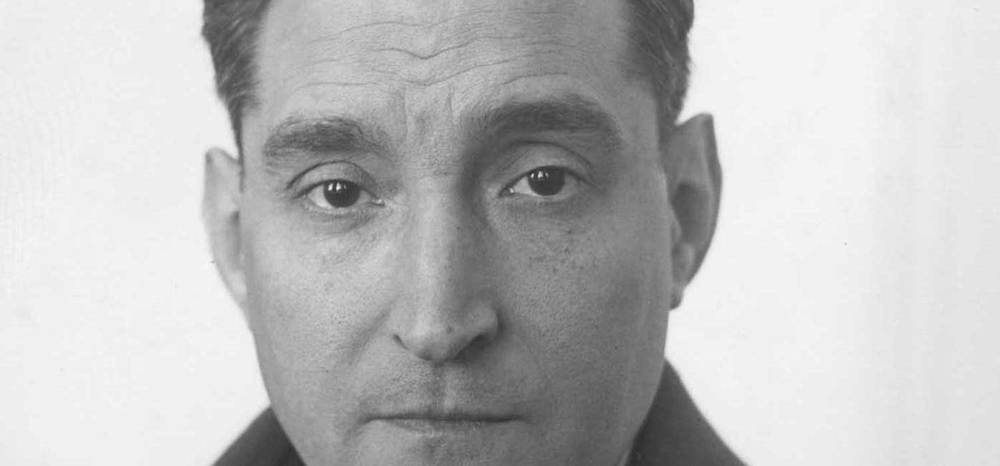

Antonio Salazar. Image via Visualizing Portugal.

History books and popular accounts of Portuguese colonialism are bi-polar: it was kinder and gentler (full of frolicking racial mixing), or more violent and corrupt than other colonialisms. In fact, I heard it just the other night at a dinner party from a hyper-educated colleague who never fails to stun me with his ignorance of all things African (and his insouciance in speaking about the continent and dynamics there despite not knowing).

But sexual expediency (i.e., lots of white male settlers and few female ones) shouldn’t be taken as softening the blow of structural violence. Césaire’s Discourse on Colonialism reminds us of the double-edged sword of colonial violence. We are all less for it.

António Oliveira Salazar founded Portugal’s New State dictatorship in 1933. Some historians like to argue over whether it was fascist or not. And these days, some Portuguese remember him fondly. He presided over the late colonial administrations in Portugal’s African colonies.

In their book Angola 61 Guerra Colonial: Causas e Consequências O 4 de Fevereiro e o 15 de Março (Alfragide: Texto Editores, 2011) Dalila Cabrita Mateus and Álvaro Mateus had this to say about Salazar and the Acto Colonial (the Colonial Act passed in 1930 but a key part of Salazar’s 1933 constitution, which made the colonies part of the Portuguese empire):

In the first place, the doctrine of the racial superiority of the colonizers, for whom the colonial expansion would be a right for the racially superior, destined to dominate. ‘We should keep on more efficiently and better organizing the protection of the inferior races,’ said Salazar in 1933. And in 1957 he repeated: ‘We believe that there are races, decadent and behind, if you will, that, in relation to whom, we have the obligation to bring to civilization.’ Otherwise, in practice, he behaved like the most common racist. Franco Nogueira [a Portuguese minister and diplomat] remembers that, in June 1965, during a secret visit of Moïse Tchombé to Lisbon, Oliveira Salazar confided in him: ‘I liked the man. Look, we should promote him to being a white.’ (pp. 26-27).

“We should promote him to being a white.”