Nelson Mandela’s environmentalism

The first African head of Greenpeace International, Kumi Naidoo, on how the world could best do justice to Mandela.

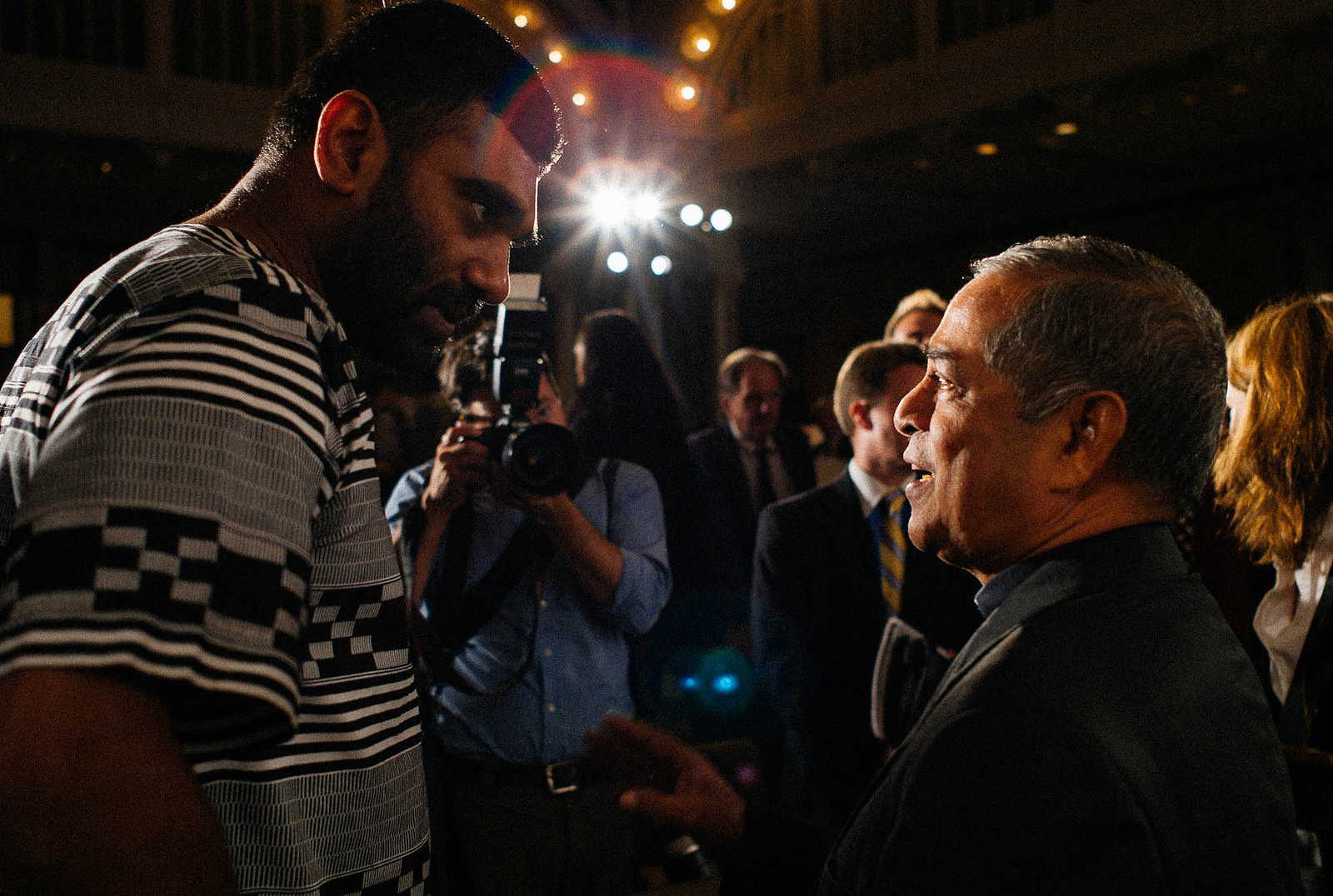

Kumi Naidoo (left) during Climate Week New York 2009. Image by Mat McDermott, via Flickr.

- Interview by

- Annie Paul

I recently had the opportunity to interview Kumi Naidoo, the first African head of Greenpeace International. Born in Durban, South Africa in 1965, Naidoo became an anti-apartheid activist at the early age of 15, something that eventually forced him to go underground before fleeing the country. Among other things I asked him about the shift to embracing environmentalism after having been such an ardent campaigner for human rights, the difficulties of leading an organization hitherto dominated by Euro-Americans and what the Russian detention of the Arctic 30 means for activism in general.

On December 5, the day Nelson Mandela finally died, I was in Amsterdam with Kumi Naidoo, a close South African friend of many years standing. In between hundreds of requests for his comments from global media I managed to sneak in an interview. Of course, Kumi and I first spoke about what Mandela’s legacy means for him. Kumi then talked about his role as Executive Director of Greenpeace International, about the predicament of the Arctic 30 who were still in captivity in Russia then and other environmental issues.

Kumi, you knew Nelson Mandela personally, you’ve had experiences with him, you are from South Africa, and I heard you in the BBC interview a moment ago saying something about how you thought top that point for me?

Mandela was very keen not to be understood as an exceptional person. In 1995 when I was heading the Adult Literacy Campaign in South Africa I took kids and adult learners to the Parliament to meet Madiba on International Literacy Day. They were excited to have their picture taken with him—the image was to become a poster for our campaign to promote adult basic education—but everyone was anxious; they were asking me what they should say and how they should approach meeting the President! The main line that people had prepared, the kids, and even the adults that were there, was something like, “Thank you, Mr. President,” or, “Thank you, Madiba, for taking time. We know how busy you are.” But when Madiba emerged from his Cabinet meeting he turned the tables. He walked in and thanked everyone for taking the time to see him. “I know how busy you all are and I thank you for taking time to meet me,” he said. In that moment he closed the gap. He was just a human being, a person like them, and everyone relaxed. Within a minute, that sort of thing about the leader and the lead, the gap was closed, and that’s a rare thing.

One of the things that I noticed with my own eyes was his ability to engage with kings and queens and heads of state on the one hand, and his ability to engage with ordinary people, equally comfortably. For example, I first met him when I was in my late 20s, in 1993. I was helping facilitate an African National Congress (ANC) workshop to plan its media strategy. I went down to meet him for the first time and you know me I got stupid… I just choked. I said, “Hello Madiba, it’s a real honour to meet you,” and I couldn’t get another word out. Just that one sentence. So during the workshop, he quietly, didn’t make a big fuss of it, quietly asked, “Can I go and say thank you to the people who prepared the food, and the workers of the hotel?” And I followed and I watched what he did and he basically shook everybody’s hands in the kitchen and said thank you to everybody.

I’ve come across a lot of people in my life who talk about poverty and talk about the poor, but you rarely have a sense that it matters to them to the point at which they will be willing to sacrifice something. Yes, they feel a sense of solidarity, but when you speak about the poor, that you actually celebrate the eloquence of the poor, the tenacity of the poor, the perseverance, courage… I mean, to survive poverty is… You know, many people theorize poverty, but so many elements of poverty, individually, for most people who theorize about poverty would be really difficult to even comprehend the individual things. Just take homelessness. If you are homeless, what does it mean not to have a post box where people can contact you; what does it mean not knowing where you’re going to sleep at the end of the day; what does it mean not having a place where you can store what little you might possess. So dealing with homelessness in itself is a huge thing for most people who are commentators [on] or benefactors to poverty. Then you take an issue like living with HIV/AIDS… I mean, you know, where health care is difficult… where people have to struggle for access to antiretrovirals and some still don’t have access to them and all of that, and just confronting that alone, for most people, would be a major challenge. And then you got things like educational deprivation as a result of a conscious apartheid strategy, where the founder of apartheid, Verwoerd, once said, and I quote, “Blacks should never be shown the greener pastures of education, they should know that their station in life is to be hewers of wood and drawers of water.”

I want to speak about you being an Indian South African, and that people don’t realize that many Indian South Africans participated in the ANC and in those struggles against apartheid. For instance I was quite surprised to see that this cellmate of Nelson Mandela was another Indian South African: Ahmed Kathrada.

In fact, several South Africans of Indian origin were in Robben Island with Nelson Mandela. There was Mac Maharaj, Billy Nair, who spent twenty years there, and Zed, Uncle Zed we used to call him—he spent fourteen years. Yeah, many, and disproportional to the size of the population in terms of this thing, but it was because of the legacy of Gandhi. During all of that there was quite a strong spirit of resistance in the community. Mandela was fond of Gandhi in terms of his life and work and writings, but the apartheid state, like all colonial regimes, maintained control by divide and rule, and in South Africa, the main form of divide and rule was on the basis of race, and not just that but also on the basis of language, so it wasn’t that it was just white, Indian, African, coloured, as they would’ve called it, but the African community was, the black African community were then broken up into Zulu, Xhosa, Tswana and the other African languages… your language and culture.

So there were people like myself who came through the liberation struggle, who were first influenced by Steve Biko, and were resisting the divisions of apartheid which were also historical and cultural divisions. Distinctions, let’s say, because obviously the people who came as indentured servants from India have a different history versus those who came to be defined as Coloured, whose numbers are in excess of three million…So, given all of these different influences, our response, those that came through the struggle like myself, when the state used to say white and non-white, we said we didn’t want to be non anything. So black then became the unifying identity. And Steve Biko’s big contribution was in the way that he defined black consciousness. He defined it as everybody who wasn’t benefiting from the privileges of white citizenship, and the ANC drew on and embraced that as well, and so for me my identity is very much first and foremost…

A black identity, as a black person?

Today, given the journey I’ve traveled, my first identity, it might sound silly but, is as a human being who is not bound by any man-made boundaries, but my second biggest identity is as an African whose identity is fundamentally linked to the African continent as a whole, and third it is South African, and then fourth, I would say, as a South African of Indian origin, and I don’t see any of those in contradiction. I think that they enrich each other in different ways.

Let’s talk about the fact that you are now Executive Director of Greenpeace International which is interesting in itself because you would be the first… I don’t want to say, non-white person to be in that kind of position, but person from the South, let’s say, representing completely new populations globally. Has this been a challenge? The fact that Greenpeace was previously a very kind of white European, or European-origin dominated organization, or is that a wrong perception?

No, historically, that’s the reality. It started in Canada and moved to the US and Europe and Australia and so on, but Greenpeace actually has been operating in the global south for a long time with strong leaders emerging from those parts of the world who are into global leadership roles as well, but still that is not the majority of the experience. It’s still an area we are committed to making more progress in. And one of the things that I’ve been working on is strengthening our presence in the poorer parts of the world, parts of the world where if we don’t get it right, such as India, China, Brazil, Nigeria, South Africa and so on, with big population sizes, then you know we can get every country in Europe to go to clean green energy, but that’s not going to cut it, because the population sizes in the developing world are mushrooming… Just from a very basic doing the math, it makes sense to invest more there and to strengthen our ability to encourage those countries not to follow the same dirty energy path that today’s rich countries built their economies on.

This is not easy to do, because, justifiably, developing countries who have significant access to the remaining fossil fuels are saying, well, why should we not burn it and build our economies in the same way that the others did. But we are saying, the problem is that then you build your economies, and the economies and the infrastructure are going to collapse, because by just continuing to burn fossil fuels, the impacts of climate change are going to become more and more real. And it’s not a question of us saying that, oh, some time in the future we are going to see climate impacts, we are seeing climate impacts in many parts of the world. Today, in many parts of Africa, and in many small island states, for example, people don’t need climate scientists to come and tell them that climate change is happening and its real. People’s daily lived experiences; rains coming at the times that they didn’t; records that are being broken in terms of hottest temperatures and coldest temperatures. We are seeing storm strength and ferocity, height and velocity increasing to extents that we barely have another recorded moment for. Changes are happening. We can see in the Arctic where the minimum sea ice level last year broke its lowest level.

Sea ice level?

Where there was the lowest level of sea ice. Sea ice serves as the refrigerator or air conditioner of the planet, it plays a key role in climate regulation, and so in that sense, the stakes are very high. At Greenpeace, the reality on the ground has helped to show why we need to win in places like the Philippines and so on, and so resources are shifting but its slower than I would’ve hoped, and the changes could be even bigger than I would’ve hoped. But change is the art of the possible. We don’t have the luxury of saying, okay folks, we’re going to engage in an internal change process now, so let’s think about how to make the most fundamental transformative changes to be as effective as we can, and bring all energies to bear on that.

We are just running out of time, on climate especially, we have to be able to act internally and make the internal changes that we need to make, and the cultural changes that we need to make to be as fit for purpose as we can, and to be as global as the challenge that we are seeking to address. On the other hand we’ve got to continue to fight on the outside at the same time and continue to win as many big and substantial victories to try to reverse the trajectory we’re on. If we continue the way we are, we’re talking about a four degree world, meaning a four degree rise from pre-industrial levels, and right now, its been agreed that we should keep it below two degrees.

The rise of?

Global temperatures. Average global temperatures. And at this rate, this year we passed the 400 parts per million concentration of carbon in the atmosphere, and the safe level of carbon concentration is 350 parts per million of carbon in the atmosphere. Already, we’ve hit 400. We’re in a very precarious state. Our political and business leaders are suffering from cognitive dissonance, where all the facts are there but they’re not prepared to act on it.

You were describing how urgent all these issues are, the environmental issues, and I’m wondering why this isn’t obvious to more people than it seems. For instance, in countries like Jamaica, the environment is almost considered a luxury, and people who protest on its behalf are resented, and often portrayed as being anti-development, Luddites etc, etc. Interestingly it’s often true that they ARE well off, better off than others in the societies they share.

To take my part here, I was involved in the anti-poverty movement for the better part of my life. I was the founding chair of the Global Call to Action Against Poverty, and I’m still involved in it. What I was seeing, looking at it from a short, medium, and a long-term perspective is that the poor were paying the biggest price for environmental destruction. And when you see an environmental crisis, such as hurricane Katrina in a rich country like the United States, what you see is that those folks who are better off are at least able to jump into their four-by-fours and other vehicles and drive away to safety, when the majority of the poor are left stranded, and the numbers of people that died were devastating to see in New Orleans. But then you take that and you can multiply that story hundreds of times over when we look at different environmental impacts. When I look at the issue of water, for more than ten years now, some of us have been saying that the future wars will not be fought over oil but will be fought about over water, and already you can see that happening. Water is the centre of many conflicts, including, by the way, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.

So the point I’m making is that if you look at it objectively, the traditional Western environmental movement, which includes Greenpeace, didn’t make the connection early enough between sustainability and equity, and sustainability and poverty. But to Greenpeace’s credit, by the time I arrived there in 2009, they had embraced the idea of sustainable equity or equitable sustainability, which was essentially bringing the agendas of how do we share the resources on this planet in a more equitable way, that everybody should have certain basic things like access to water, sanitation, basic education, health care, and a certain level of energy. There are 1.6 billion people on this planet who live with complete energy poverty today; they don’t have access to a single light bulb. That’s not a small amount of people. So, for me, the struggle to avert catastrophic climate change, which will wipe out all the developments whether in rich or poor countries, is the critical success factor for consolidating any development initiatives that we do, and so, if you look at Bangladesh, some investments that were done, good development work on the coastal parts of Bangladesh, are already being turned back because of sea level rise and salt water contaminating the soil and making it hard for people to grow food that they were able to grow before.

So essentially, the poor, and poor countries—even though poor countries in the main have not been responsible for that huge amount of carbon emissions—if you look at the history of burning oil, coal and gas, and when it started, the irony is that people in poor countries are paying the first and most brutal impacts of climate change. And it’s only going to get worse. So in that sense, for me, fighting climate change is fundamentally about fighting poverty, and I don’t see a disconnect there.

But you know what I find interesting, when you thing about environmental groups, action groups globally, Greenpeace comes to mind immediately, but one is hard pressed to think of any others. Why do you think that is? I mean, there are other environmental NGOs, aren’t there, who are doing important work?

Yes, there are many… WWF, the World Wildlife Fund…

But I mean one has to think a bit to recall the others…

Well, I suppose it’s because Greenpeace does take part in, does have as part of our work, peaceful civil disobedience, and that does get us into trouble with the authorities from time to time and gives us more media visibility.

As you are getting now, with the Arctic 30. What does Russia’s reaction of jailing the Arctic 30 imply for activism broadly speaking, for non-violent protests, and the like? It’s set a bad precedent, hasn’t it?

I think that there’s two ways you can look at it. One is, just the fact that it happened people will be so shocked by it and will speak out about it, not just in Russia but across the world, and in fact the opposite result might be achieved, which is that people say we really need to make sure that governments do not use such disproportionate force when there are peaceful protests, or such disproportionate use of the formal prosecuting authority. Of course, the other reaction is that people will get intimidated and so they won’t undertake protests. Both will probably be true, as realities. To be fair to Russia, by the way, it is not the only country where there has been a shrinking of civic space, specifically, and democratic space more generally.

Which are the others? China?

Oh no, even in the United States, if you look at their response to September 11: the Patriot Act, legitimizing and defending torture, engaging in extraordinary rendition, racial and religious profiling, NSA, invasion of privacy; I mean all of these things have a chilling effect on citizen participation generally, and civic activism more specifically. In Canada, we have these lawsuits, which are called SLAPP suits, Strategic Litigation Against Public Participation (SLAPP) which are suits brought by companies to intimidate NGOs and campaign groups. A state like Quebec now actually has anti-SLAPP legislation to prevent companies from doing it–that’s how big a problem it is. For example, in Canada now, a company headquartered in Quebec brings a case in Toronto, because they couldn’t have brought it in Quebec because of the anti-SLAPP Legislation. And they are charging us with a seven million dollar defamation claim.

Who?

Greenpeace.

What is that in relation to?

To the fact that we made statements condemning the activities in the Boreal Forest.

So it’s not just Russia.

I think it will not be known for some time exactly what the impact will be, but I also think its going to open up some questions about what level of risk is acceptable for activism to take, given what we face in terms of…

Repercussions.

Yes and I don’t know where exactly that will end. As regards Greenpeace, while I’m not saying we will do exactly the same action at the same place in the same way again, neither am I saying that we won’t. But we will obviously learn from this. This has been a big development for us, we will learn from it, and we recognize, as Greenpeace, that we live in a world where people are being killed and tortured and arrested and brutalized for standing up for the environment and social justice everywhere in the world, and we hope that we would be able to help contribute to the push for saying that governments need civil society, society needs active participation and so on, and that hopefully governments will embrace the perspectives of their citizens and allow peaceful protests, including those that have an element of civil disobedience.

And if you want to connect the two parts of it… Our people in Russia, first were called pirates and now are called hooligans. Nelson Mandela, Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, and many other people who stood up for freedom and justice, were also, when they were doing so, called all sorts of labels, including labels worse than being called hooligans. Terrorists and so on. But today we revere them as the greatest peoples to have walked on our planet. I have no doubt that the Arctic 30 will be seen as people who did the right thing for the world, and acted out of compassion not out of self-interest. But I hope the world will come to that realization sooner rather than later, because we are running out of time.