Chinua Achebe reflects on Biafra, but for whom?

Achebe's "There Was a Country: A Personal History of Biafra" reopens old wounds about the civil war.

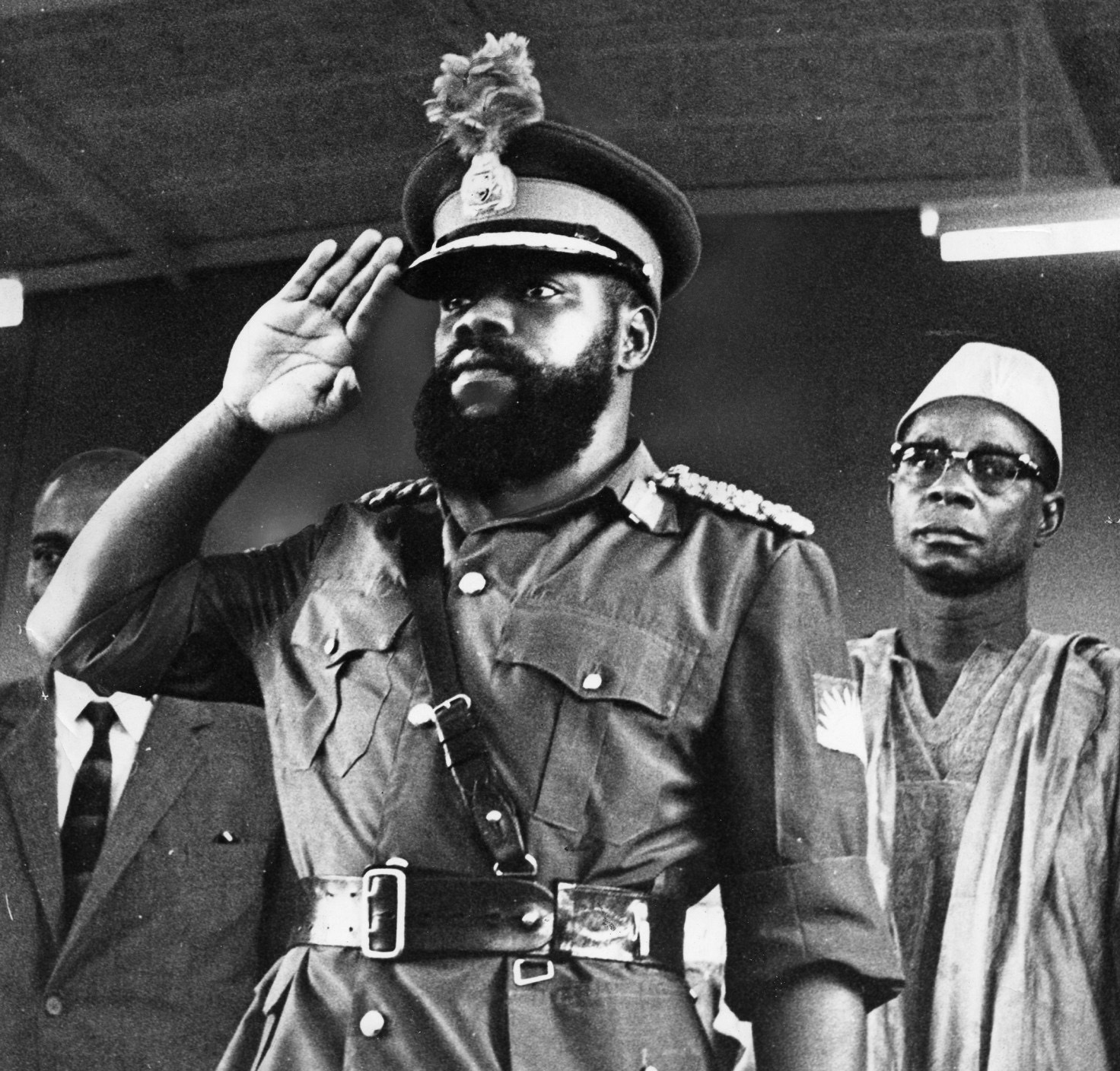

General Odimegwu Ojukwu, the military leader of the Republic of Biafra from 1967 to 1970.

It is a long time already since the Biafran War (1967-1970) to write a memoir, and it makes me wonder how affective Chinua Achebe’s narrative in The Guardian is to his audience. Achebe’s new book, There Was a Country: A Personal History of Biafra appears to have reopened old wounds and resulted in widespread debate, whether in op-ed columns, on blogs or on social media.

I question, however, if it is possible for Achebe to remain faithful to a forty-five year-old war story? While it is important to account for history for posterity’s sake, when left too long, it might decline in veracity and become romanticised. I found an example in an excerpt of Achebe’s book quoted in the review by writer (and Achebe admirer) Chimamanda Adichie, where Achebe relays the death of his beloved friend, the poet Christopher Okigbo (Achebe has described him on occasion as “Africa’s greatest modern poet”) to his family:

When I finally got myself home and told my family, my three-year-old son, Ike, screamed: ‘Daddy don’t let him die!’ Ike and Christopher had been special pals. When Christopher came to the house the boy would climb on his knees, seize hold of his fingers and strive with all his power to break them while Christopher would moan in pretended agony. ‘Children are wicked little devils,’ he would say to us over the little fellow’s head, and let out more cries of feigned pain.

I stopped. How would a three-year-old conceive of death this imaginatively? This for me appears to be an affective narration of an adult’s hurtful experience transferred to a child. Is it not possible that other narrations in the story have also been idealised? Interestingly, this “much awaited” book is supposed to be a response to the war, and perhapsto become a reference point, as there are, in his words: “little relevant literature that helps answer these questions.”

Achebe’s Guardian article, for me, seems to have ended up promoting a self-serving perspective that encourages ethnocentricity. It has furthered ethnic cyber-war on social media and online pages of national newspapers like the The Nation, Punch, and in the Vanguard Newspaper, where a review of the book generated hate comments like:

You will never see me in a Yoruba Church, I don’t care if the pastor’s name is Jesus. This people lie like their father the devil, do you wonder why even the Hausa hates them, is not ironically that despite everything, Hausa’s still find Igbos more credible and trustworthy than Yorubas, even the south-south people can no longer trust this debased Yoruba characters, archtechs of crime and yet like the devil, always accusing others of sin, when they live and dine with the devil everyday. OGBONI-YORUBA MEANS SATAN WITH YORUBA, THE ONLY IGNORANT RACE THAT HAS PATH WITH THE DEVIL IN NIGERIA. (sic)

Some of the comments in The Guardian suggest that Achebe is propagating Igbo propaganda, especially, with his slight on Chief Obafemi Awolowo, who is accused of encouraging starvation during the war with his now infamous quote: “All is fair in war, and starvation is one of the weapons of war. I don’t see why we should feed our enemies fat in order for them to fight harder.” Ironically, this action was commended by Alex Ekwueme in a Vanguard article in 2010 as an act that displayed Awolowo as “a prudent manager of human and material resources by maintaining strict fiscal discipline in government spending and equally ensured that the Federal Government did not borrow money to fight the war.”

The Biafran War defined many things about Nigeria’s future. My father once told me that “we stopped being Nigerians after Biafra.” Many Igbos believe they have always been marginalised and were never really a part of the country before the war and even after. The debate on the marginalisation of the Igbo deepens each time the Federal Government is accused of attempting to exterminate Igbos during the Biafra war. Forty-five years since the war, this dirge is again revived in Chinua Achebe’s Guardian contribution.

Perhaps there are those who still see Achebe as a credible source for understanding Nigeria’s history and even that his newly published book would enlighten Nigeria on the ethnic divide since the 1966 war, it is important to note that it is not just the Biafran War that is missing in Nigeria’s school curriculum at this time; history and social studies have for a long time not been taught to students.

What is worrisome is that forty-five years after this war, it is difficult to know who exactly Achebe’s audience is: the Nigerian who lacks history or those with a manipulated history told to them by foreign media and regurgitated by the local media.